Identity and student mental health

School mental health done well recognizes and affirms the identities of every student, regardless of their background or experiences. Identity-affirming school mental health addresses inequities and creates an inclusive and supportive environment for every student.

On this page:

Why this is important

- Identity and mental health are inextricably linked. Who you are affects how you feel. When your identity is affirmed, reflected, and celebrated, you’re more likely to feel a strong sense of positive mental health, well-being, and connection. If your identity is ignored, excluded, or misunderstood, or if you experience racism or oppression, you can suffer emotionally and must work much harder than others to gain a sense of well-being.

- Mental health is often viewed through the lens of white, Eurocentric culture, and interventions tend to be rooted in Western practice and study. Many of these approaches emphasize individual change and skill development. While this can be helpful, a more identity-affirming approach to school mental health also considers the role of the wider school/community environment in effecting lasting positive change. This involves optimizing community and collective strengths and supports and addressing structures that affect the mental health of individuals and groups who are racialized and marginalized.

- When school administrators reflect deeply on their own personal values, beliefs, and biases, and engage staff to do so, they are setting the stage for schools to move toward providing mental health support that is identity-affirming and culturally responsive to every student.

- When schools and boards dismantle and remove racism and oppression; engage and partner with students, parents/caregivers, and community; amplify diverse student, parent/caregiver, and community perspectives; and respond with differentiated and identity-affirming supports and practices, they are working toward supporting every student.

The relationship between identity and mental health

School context matters in how students come to see and understand their identity and how they experience ways that others view their identity. Each day, schools have the opportunity to be intentional places that nurture the whole child – where diversity is valued and meaningfully woven into the culture, adults are a source of positive and caring regard for every student, curriculum is culturally relevant and inclusive, and practices, policies, procedures, and structures amplify (rather than diminish) cultural ways of knowing and being.

- Identity refers to the various aspects of a person’s sense of self, as they define it. These aspects can include but are not limited to race, gender, sexuality, culture, religion, faith, health/mental health, and socioeconomic status. Internal and external factors – including personal experiences, societal norms, and cultural expectations – shape identity. Identity, and the parts of ourselves that we emphasize, can change over time. It is also complex because our personally defined identity sometimes conflicts with how others see us.

- Oppression refers to the systemic mistreatment of and discrimination against certain groups based on aspects of their identity. Privilege refers to the advantages and benefits that certain groups receive because of their identity.

- Individuals can experience oppression and privilege based on different aspects of their identity. For example, one person might experience privileges due to their social location and power in a school administrator position and experience oppression related to their race, gender, or sexual orientation. Intersectionality highlights the complex ways these experiences can intersect with and affect one another.

- recognizes that individuals are not defined by one singular aspect of their identity but rather by the complex ways in which the aspects of their identity (e.g., race and gender) intersect and interact with one another. This concept is fundamental in understanding how different forms of oppression, such as racism, sexism, and homophobia, can compound discrimination and marginalization for individuals and groups.

Race, culture and student mental health

One of the most complex and critical considerations is the intersection of race, culture, and student mental health. To facilitate the introduction and use of quality, differentiated, and identity-affirming mental health supports, school administrators need an understanding of both mental health and how it is affected by race and culture, as well as the unique mental health needs of Black, Indigenous, and racialized students.

- Race is a social construct that has real-world impact. The racial group one associates with often forms a very central part of one’s identity.

- Dubious history and science has been used to justify harmful policies and negative stereotypes, which has left a legacy in the education system, and therefore, race cannot be ignored in school considerations of student mental health.

- Culture is open to multiple interpretations; it generally refers to a set of values, beliefs, and behavioural expectations shared by people within a geographical origin. Cultural groups typically share language, religion, cuisine, and arts (among other things).

- Cultural teachings are passed from generation to generation and reinforce group norms – what to eat, how to dress, etc. More importantly, cultural teachings tell one how to act typically, thus also defining atypical behaviour.

- In Ontario, students represent many cultures, both Indigenous and settler. It is overly simplistic to suggest that all children and youth from the same geographic or cultural origins share the same cultural influence.

- All societal institutions, including schools, are shaped by and reflect the dominance of white, Eurocentric culture. Mental health in education is consequently viewed through the lens of white, Eurocentric culture.

- The Eurocentric perspective affects how mental health and illnesses are defined, what are considered appropriate or acceptable ways of coping, and how to address/treat mental health problems effectively. This dominant and biased view ignores how other cultures describe, cope with, and treat/address mental health and illness (Fuentes et al., 2019).

Marginalization and student mental health

There is evidence that individuals with marginalized identities face disparities and disproportionalities in both the likelihood of experiencing a mental health concern and in accessing treatment.

- Racial or race-based trauma is a mental and emotional effect that stems from encountering racial prejudice, discrimination, racism, and hate crimes.

- The experience of racial discrimination can lead individuals to cope and adapt in various ways, including hypervigilance, avoidance, and numbing.

- Studies that follow children and youth over time have shown that experiencing racial discrimination is associated with later mental health and behavioural problems.

- Male Black youth who were exposed to increasing racial discrimination in early adulthood faced a significant aggravation of symptoms of depression and anxiety into their 30s. Racial discrimination is significantly associated with depression and anxiety among Black adolescents. Perceived racial discrimination is also associated with elevated suicidal ideation, suicide planning, and attempted suicide among racial-minority American adolescents. Canadian Black youth identify racial discrimination as a key contributor to mental health challenges. For Canadian-born Black adolescents and Black immigrants, reported racism has increased from 2003 to 2018, especially among girls; those who reported racial discrimination were significantly more likely to also report extreme stress, suicidal thoughts, and suicide attempts.

- 2S/LGBTQIA+ students face unique mental health challenges related to homophobia, transphobia, and discrimination. Higher rates of suicidal behaviour are experienced by 2S/LGBTQIA+ young people, and particularly those who identify as transgender or gender diverse, especially when they experience a lack of family acceptance.

- Newcomer students experience a number of barriers on a structural, provider, and individual level. On a structural level, students enrolling in a new school may find the environment complex and difficult to navigate, especially if newcomer students are not aware of the available mental health supports or how to access them within schools. On a provider level, there is a lack of diversity and lived experience among school staff, in addition to gaps in cultural competency to effectively support newcomer students. Lastly, on an individual level, there may be language barriers, which can hinder effective communication between newcomer students and school staff.

- In Ontario, francophone children and youth encounter persistent and compounding obstacles in accessing linguistically appropriate mental health services in both urban and rural communities.

- Racism and discrimination that intersects with barriers like poverty (including food and housing insecurities), access to care (particularly language barriers and transportation), and poor family and social supports contribute to mental health challenges.

To create a supportive school environment, school administrators and staff must acknowledge systematic inequities in society and need to be aware of the impact of oppression and racism on the mental health of students, colleagues, parents/caregivers, community members, and themselves.

Special education and student mental health

When developing and delivering student mental health supports and services, consideration should be made to ensure that lessons and activities are inclusive of every student, including those with special education needs. The presentation of mental health symptoms can fluctuate over time in children and youth, and an underlying neurodevelopmental disorder or a physical or learning disability can further complicate the presentation of symptoms. Students with special education needs may encounter obstacles in accessing mental health support, as their mental health needs might go unrecognized or be overshadowed by the primary emphasis on developing and implementing an individualized learning program to address their specific educational requirements.

- Students with special education needs are at a higher risk of mental health challenges than their peers without disabilities.

- Students with special education needs may require tailored mental health supports that are responsive to their unique needs and challenges.

- The intersection between learning needs, neurodevelopmental disorders, and mental health needs can be extremely complex, and at times mental health problems can be masked behind more prominent learning, behavioural, or developmental challenges, and vice versa.

- Providing mental health supports and interventions that are inclusive and responsive to students with special education needs can promote their overall well-being and success in school.

- Addressing mental health challenges and promoting positive mental health can have a significant impact on the academic success of students with special education needs.

Feeling safe, supported, and included is essential for everyone’s mental health. Students requiring special education supports and services may need environmental accommodations and personal supports to achieve the same feelings of safety, support, and inclusion as their peers. When a student is excluded, targeted, or bullied, it can harm their mental health. According to the Canadian Survey on Disability (2017), 42% of Canadian youth with disabilities have experienced bullying at school related to their disabilities.

School staff are familiar with efforts to nurture a culture of understanding, acceptance, inclusion, and kindness. Your school-wide efforts to celebrate differences through lessons and activities go a long way to supporting the mental health of students with special education needs.

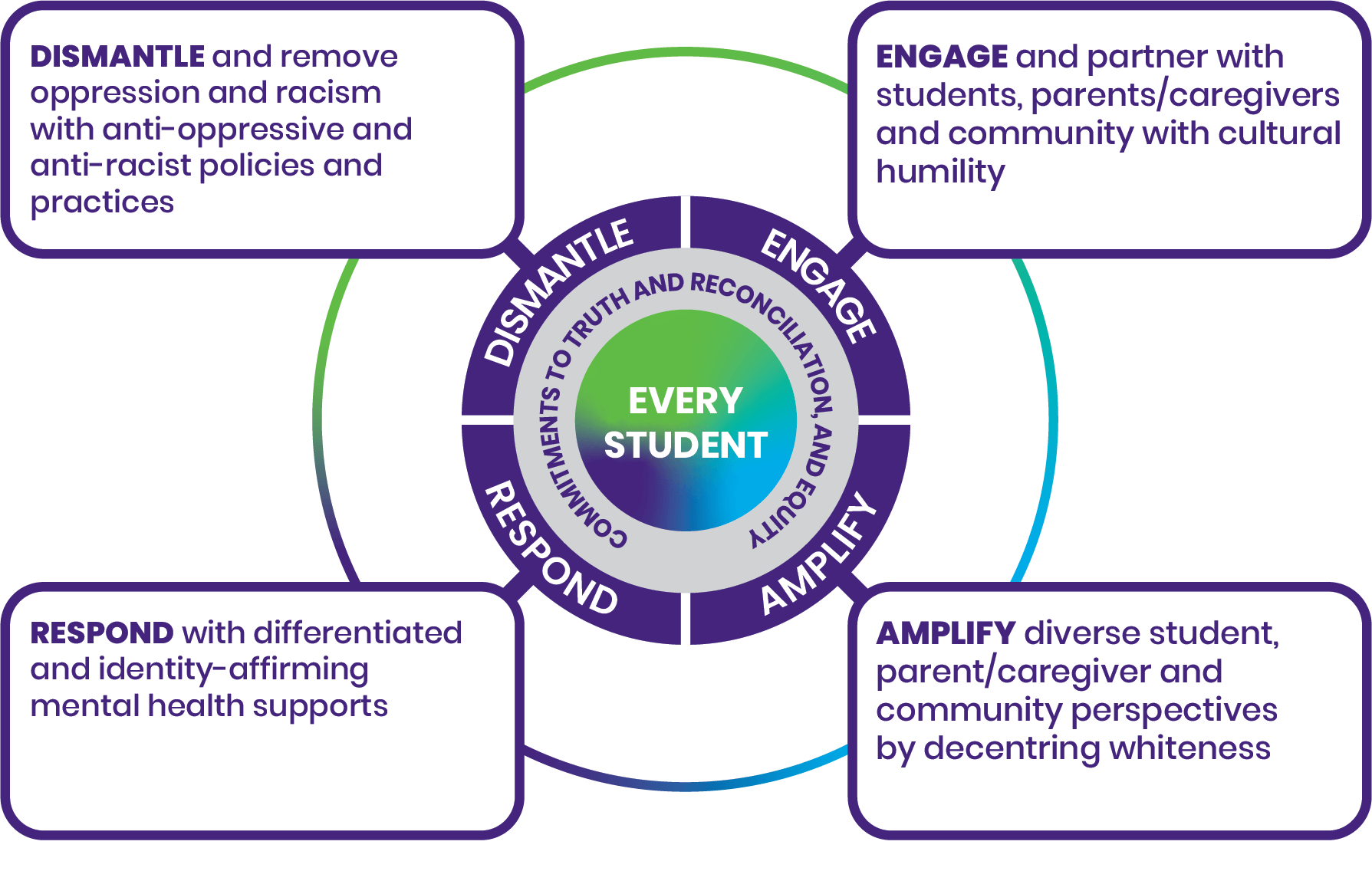

Identity-Affirming School Mental Health Frame

The very centre says every student. A ring around the centre circle says commitments to Truth and Reconciliation, and equity.

The next ring out has the words dismantle, engage, amplify and respond. Each word expands out to a box with a definition:

Dismantle and remove oppression and racism with anti-oppressive and anti-racist policies and practices

Engage and partner with students, parents/caregivers and community with cultural humility

Respond with differentiated and identity-affirming mental health supports

Amplify diverse student, parent/caregiver and community perspectives by decentring whiteness

Identity-affirming approaches to school mental health are responsive to individual student needs and affirm intersecting and developing identities. This approach contributes to and benefits from the wider efforts in school boards and schools to address oppression and marginalization, and to work toward Truth and Reconciliation, equity, and justice, especially for those historically and presently oppressed. It requires time, reflection and planful action for school administrators to move from current practices to an embedded and integrated approach to identity-affirming school mental health.

The goal of the Identity-Affirming School Mental Health Frame is to guide boards and schools as they thoughtfully reflect and plan resources and supports for their respective communities that meet the unique needs of every student.

Considerations and approaches for identity-affirming schools

Explicit commitments to Truth and Reconciliation and equity

- Make explicit personal and professional commitments to Truth and Reconciliation and equity. Take time to learn and reflect on the intersections of Truth and Reconciliation, equity, and mental health and well-being.

- Be aware that it’s harder to recognize and understand injustices and inequities that our identities and positionality protect us from. Critically examine your identity and how it influences your role in creating mentally healthy schools. This work begins with knowing your identities and reflecting on positionality, power, and privileges and how that shapes your views on such things as diversity and mental health. Think about how you might invite staff to do the same.

- It is important to validate and affirm the multiple and intersecting identities of students, including their mental health experiences. Understanding that the intersectionality of multiple identities like race, culture, gender identity, age, differing abilities, etc., can overlap and intensify

- Be critically aware of the messages sent that devalue specific populations and centre whiteness (e.g., learning environments that celebrate only Eurocentric scholars, experiences, holidays, etc., and ignore those of racialized students).

- Lead with a strength-based approach and focus on student interests and competencies when considering students’ mental health needs.

- Consider how preconceived notions of identity markers may impact student experiences. Each student is unique and it’s important to consider the whole child (i.e., a student is more than just their diagnosis)

Dismantle and remove racism with anti-oppressive and anti-racist practices related to school mental health

- Be actively anti-racist and anti-oppressive.

- Be guided by the needs of those being marginalized, not those who resist equity commitment and changes.

- Listen to and believe those who share their experiences of inequities.

- Act directly to address and eliminate racism and oppression when it’s been identified.

- Plan for barriers and resistance and never allow them to deter you from your commitments.

- Embrace critical feedback along the journey, knowing with humility you won’t always get it right. In these cases, follow principles of reconciliation and reparation to restore relationships and address harm.

- Operate from a space where you recognize that identity is a determining factor in access because of deeply rooted structural barriers that obstruct educational equity. Seek to understand the socioeconomic and political contexts that continue to negatively affect and disadvantage students, families, and communities. Actively address all “isms” and phobias that signal discriminatory behaviours, and remove barriers and forms of oppression that hinder students’ success to ensure educational equity for every student.

Critically evaluate school traditions, practices, and procedures and ask for input from students, parents/caregivers, communities, and staff to identify needed changes.

Engage and partner with students, parents/caregivers, and community with cultural humility

- We must examine the biases we’ve internalized that can divide us and cause harm as we live and socialize in a society that devalues certain identities. This ongoing, critical, self-reflective practice requires school administrators and all staff to position themselves as open learners in the service of supporting every student.

- Commit to building trust. Recognize that schools are not equally safe spaces for all students, parents/caregivers, and families. Trust is not automatic – it takes time, effort, and humility to build and sustain. Be mindful that historially, the education system has failed to build trust with many marginalized communities because of discriminatory practices, racist policies, etc.

- Work alongside students, parents/caregivers, and community partners to plan and implement identity-affirming mental health supports in schools and classrooms. Check in regularly to ensure that partners are feeling heard, their perspectives are respected, and their ideas and suggestions are incorporated.

Amplify diverse student, parent/caregiver, and community perspectives by decentring whiteness in school mental health

- Listen to parent/caregiver concerns and honour their expertise around their children’s well-being so you can work together to find better ways forward and are inviting new relationships that facilitate healthy home–school communication more generally.

- Take time to listen and learn about practices in community spaces that help to build self-love, culture, belonging, and relationship. Work with partners to bring these ideas to the school setting, amplifying their good work (being careful not to appropriate the practices, but instead offering a way for cultural/community practitioners to share their leadership). Creating space facilitates agency, wellness, and hope.

- Actively decentre whiteness. Actively redistribute power to favour and prioritize diverse ways of knowing, being, and understanding. Recognize that the work of decentring whiteness applies to every school community, regardless of the racial and cultural makeup of the students in the school. Not decentring whiteness will continue to perpetuate Eurocentric perspectives as superior.

- Centre student voices/perspectives. Collaborate with students and use authentic student voice and participation to co-create environments that reflect and honour the strengths and identities of every student. Evaluate the identity-affirming culture in partnership with students, staff, and communities who are disproportionality affected.

- Value diversity. Celebrate and honour the unique identities of students, staff, and communities daily (not only on specific days or months of recognition or holidays). The celebration and recognition of diversity can be woven throughout activities, lessons, and materials so it’s seen not as an add-on, but as an integral part of school culture and learning.

Respond with differentiated and identity-affirming mental health supports

- Consistently engage students to gather insights and perspectives on mental health needs, challenges, and responsive support mechanisms. This could be through established student advisory groups or councils, but we encourage you to look for opportunities that are informal and ongoing.

- Actively involve students in the decision-making process for mental health initiatives and programs.

- Incorporate diverse perspectives, histories, and mental health practices into mental health promotion activities that support students’ connection with their cultural identities.

- Provide resources and educational materials that are identity-affirming and culturally responsive.

- Collaborate with community organizations and mental health agencies to expand and enhance mental health resources available to students, taking into account diverse community needs.

Resources to support identity-affirming school mental health

Argenyi, M., Mereish, E., & Watson, R. (2023). Mental and physical health disparities among sexual and gender minority adolescents based on disability status. LGBT Health, 10(2), 130–137.

Assari, S., Moazen-Zadeh, E., Caldwell, C., & Zimmerman, M. (2017). Racial discrimination during adolescence predicts mental health deterioration in adulthood: Gender differences among Blacks. Frontiers In Public Health, 5.

Augustine, L., Lygnegård, F., & Granlund, M. (2022). Trajectories of participation, mental health, and mental health problems in adolescents with self-reported neurodevelopmental disorders. Disability and Rehabilitation, 44(9), 1595–1608.

Baiden, P., LaBrenz, C., Onyeaka, H., Muoghalu, C., Nicholas, J., Spoor, S., Bock, E., & Taliaferro, L. (2022). Perceived racial discrimination and suicidal behaviors among racial and ethnic minority adolescents in the United States: Findings from the 2021 adolescent behaviors and experiences survey. Psychiatry Research, 317.

Berry, O., Tobon, A., & Njoroge, W. (2021). Social determinants of health: The impact of racism on early childhood mental health. Current Psychiatry Reports, 23(5).

Cave, L., Cooper, M. N., Zubrick, S. R., & Shepherd, C. C. J. (2020). Racial discrimination and child and adolescent health in longitudinal studies: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 250, 112864.

Comas-Díaz, L., Hall, G. N., & Neville, H. A. (2019). Racial trauma: Theory, research, and healing: Introduction to the special issue. The American Psychologist, 74(1), 1–5.

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299.

Dumas, M. J. (2016) Against the dark: Antiblackness in education policy and discourse, Theory Into Practice, 55(1), 11-19

Fuentes, A., Ackermann, R. R., Athreya, S., Bolnick, D., Lasisi, T., Sang-Hee, L., McLean, S. & Nelson, R. (2019). AAPA statement on race and racism. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 169, 400–402.

Hoy-Ellis, C. (2023). Minority stress and mental health: A review of the literature. Journal of Homosexuality, 70(5), 806–830.

Lemay, R., Kelly, L., Marion, C. G., & Sundar, P. (2017). Pourquoi pas? Strengthening French language service delivery in Ontario’s child and youth mental health sector. Ontario Centre of Excellence for Child and Youth Mental Health.

Little, W. (2023). What is culture? In Introduction to Sociology (3rd Canadian Ed.), OpenStax.

Meyer, I. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697.

Okoye, H., & Saewyc, E. (2021). Fifteen-year trends in self-reported racism and link with health and well-being of African Canadian adolescents: A secondary data analysis. International Journal for Equity in Health, 20(1).

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2013). Supporting minds: An educator’s guide to promoting students’ mental health and well-being.

Pachter, L., Caldwell, C., Jackson, L., & Bernstein, B. (2018). Discrimination and mental health in a representative sample of African-American and Afro-Caribbean youth. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 5(4), 831–837.

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2020). Social determinants and inequities in health for Black Canadians: A snapshot.

Rose, R., Howley, M., Fergusson, A., & Jament, J. (2009). Mental health and special educational needs: Exploring a complex relationship. British Journal of Special Education, 36(1), 3–8.

Russell, S. T., & Fish, J. N. (2016). Mental health in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth. Annual review of clinical psychology, 12, 465–487.

Russell, S. T., Pollitt, A. M., Li, G., & Grossman, A. H. (2018). Chosen name use is linked to reduced depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and suicidal behavior among transgender youth. The Journal of Adolescent Health: official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 63(4), 503–505.

Salami, B., Idi, Y., Anyieth, Y., Cyuzuzo, L., Denga, B., Alaazi, D., & Okeke-Ihejirika, P. (2022). Factors that contribute to the mental health of Black youth. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 194(41), E1404–E1410.

Sim, A., Ahmad, A., Hammad, L., Shalaby, Y. & Georgiades, K. (2023). Reimagining mental health care for newcomer children and families: a qualitative framework analysis of service provider perspectives. BMC Health Services Research, 23 (699).

Tatum, B. (2017). Why are all the black kids sitting together in the cafeteria: And other conversations about race. Basic Books

Thapar, A., Livingston, L. A., Eyre, O., & Riglin, L. (2023). Practitioner review: Attention‐deficit hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder – the importance of depression. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 64(1), 4–15.

The Trevor Project. (2022). 2022 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health.

Yang, P., Hernandez, B., & Plastino, K. (2023). Social determinants of mental health and adolescent anxiety and depression: Findings from the 2018 to 2019 National Survey of Children’s Health. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 69(3), 795–798.