Student Engagement Toolkit

The Student Engagement Toolkit offers practical strategies for supporting diverse student leadership styles and promoting mental health initiatives within school and system settings. It addresses the interest among students to participate in mental health leadership roles and provides guidance for creating environments that support student engagement in promoting mental health and wellness.

Introduction

This Student Engagement Toolkit has been created alongside a working group of educators, administrators, support staff, board mental health leaders, and students with experience in student engagement initiatives within school and system settings. In #HearNowON for 2021 , a provincial student voice research initiative by School Mental Health Ontario (SMH-ON), students shared that they want opportunities to learn and practice new skills to support their leadership and participation. More specifically, 70% of respondents were interested in getting involved in mental health leadership. 87% percent of students indicated they were interested in getting involved at their school, 46% in their community, 36% at their school board or school authority, and 24% in the province. Students emphasized the importance of diverse representation in student leadership positions and the inclusion of diverse leadership styles, such as “shy leaders.”

This toolkit shares practices for school/board staff that are applicable to various student engagement initiatives, including those focused on mental health and wellness. The topic of mental health and well-being, and leadership opportunities can occur in many student spaces, including those not initially focused on mental health. As you move through this toolkit, consider your role in engaging students, meeting them where they are, and creating supportive environments for students to engage in school and system mental health promotion, planning, and programming.

What is student engagement?

Student engagement is an ongoing process that centres every student’s lived experience and voice, positioning them as valued experts to influence outcomes that affect them. It requires critical reflection by school and system staff to dismantle imbalanced relationships and uplift student voices in mental health planning and programming.

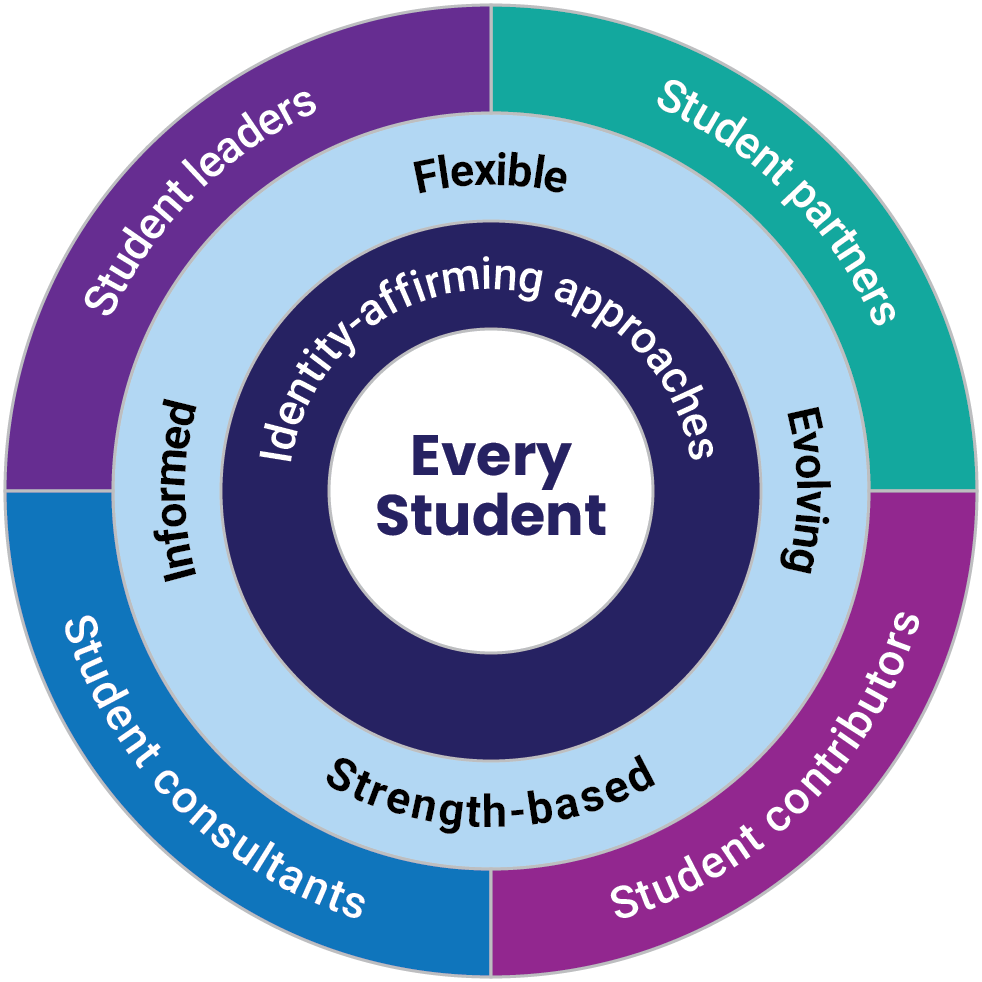

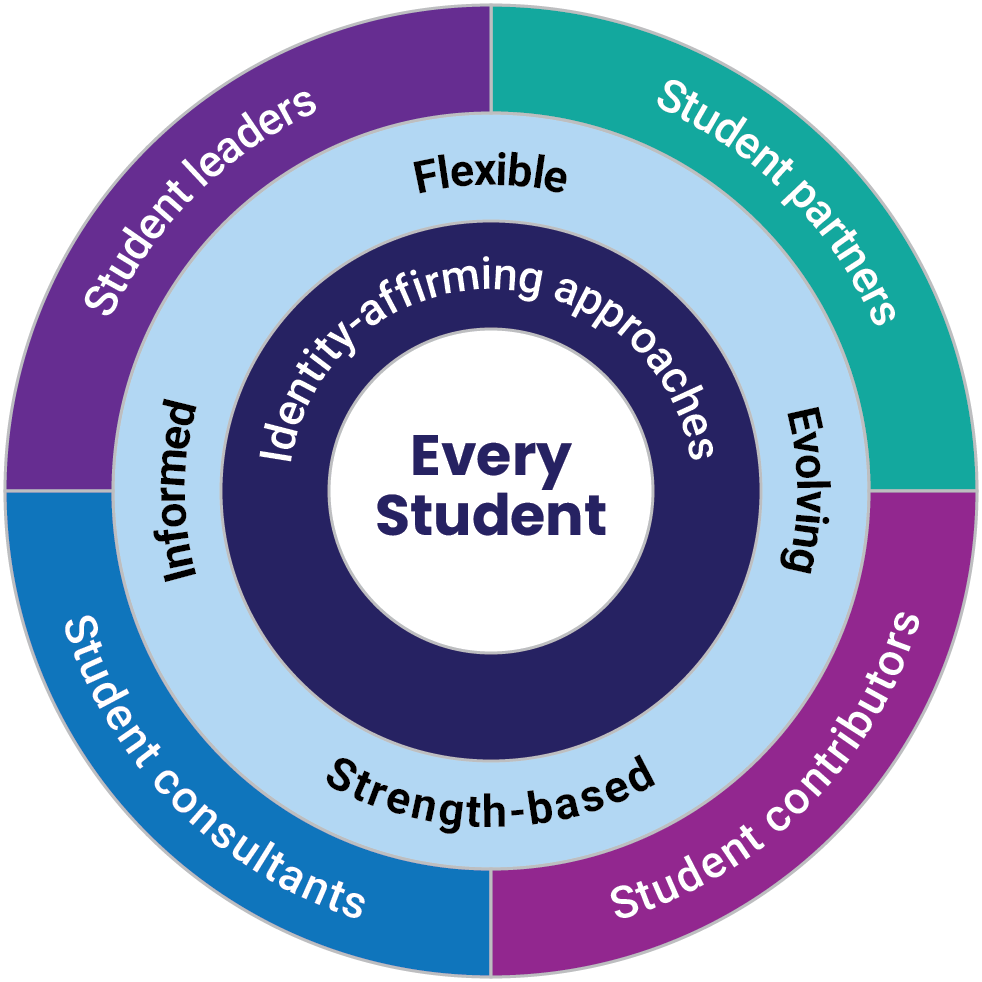

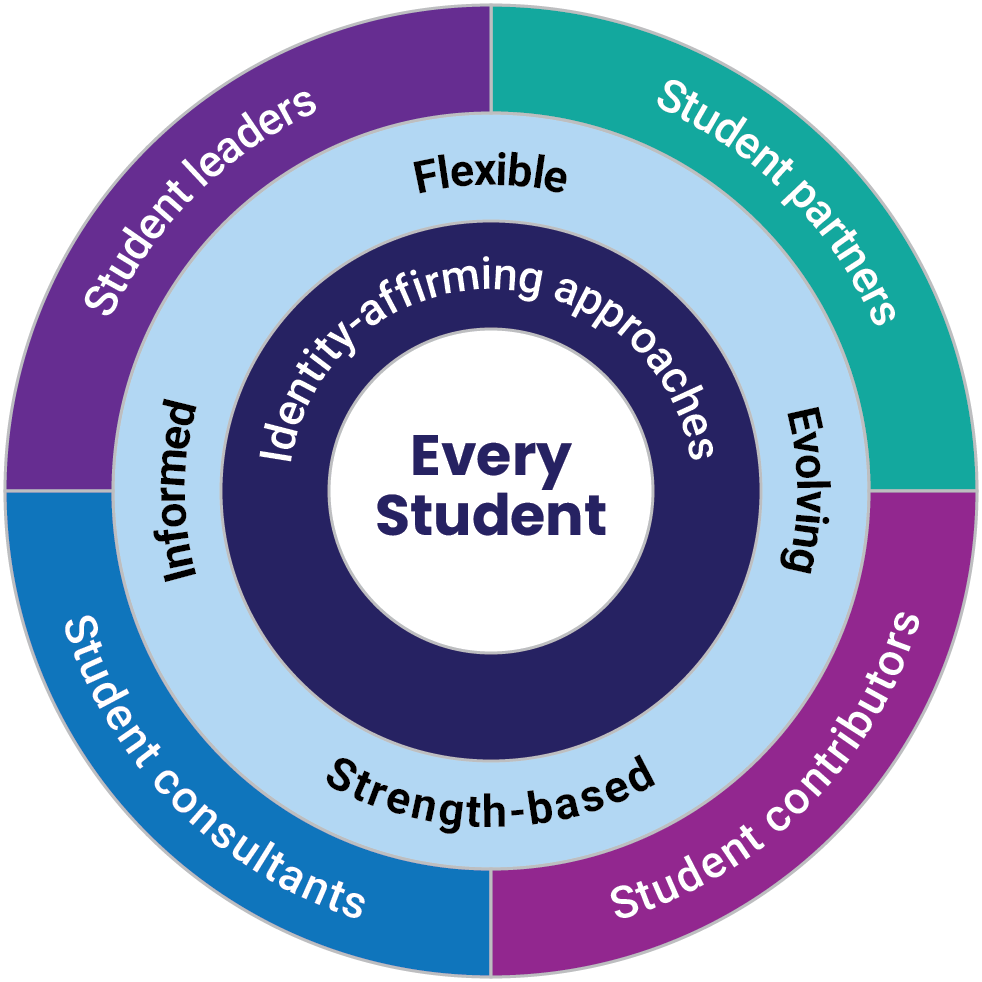

Our model of student engagement

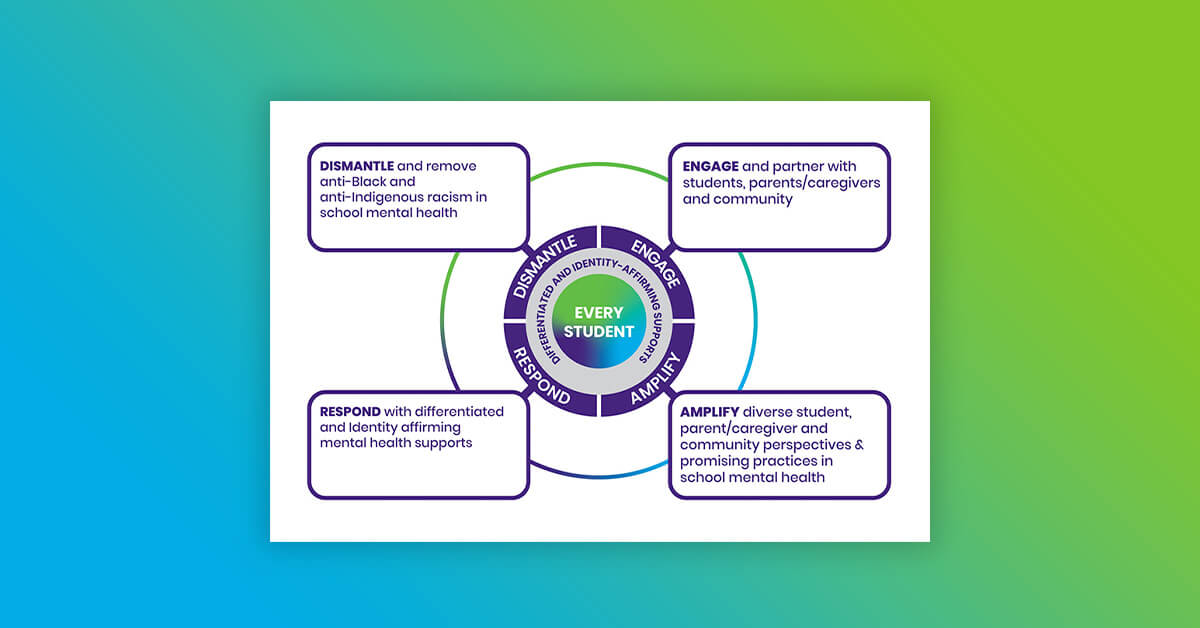

Every student

Aligned with School Mental Health Ontario’s School Mental Health Strategy, every student is at the centre of this model. Every student is an agent in defining their engagement in school initiatives.

Identity-affirming approaches

Surrounding every student are identity-affirming approaches as a foundation for meaningful student engagement. Identity-affirming student engagement recognizes, validates, and respects every student’s intersecting identities, backgrounds, and experiences.

Identity-affirming school mental health

Flexible, strength-based, informed, and evolving

The foundations of student engagement are those concepts that underscore every engagement initiative. These foundations highlight the importance of flexibility, recognizing and nurturing students’ strengths, making decisions informed by them, and adapting strategies to meet their ever-evolving needs, ultimately fostering more inclusive and impactful student engagement experiences.

See the Foundations section below

Student leaders, partners, contributors, and consultants

In this conceptualization, student engagement encompasses various degrees of engagement offering students diverse skill development, commitment levels, and influence over outcomes. Students have multiple entry points, enabling them to engage in initiatives that align with their interests and abilities.

See the Degrees section below

Meaningful student engagement at school is a primary protective factor for students’ overall well-being. Outcomes for students include:

- increased social connectedness and sense of belonging

- feeling heard, listened to, and validated by caring adults; more positive relationships with adults

- increased self-esteem and self-confidence

- increased sense of agency

- experiential learning opportunities and skill development

(Dworkin et al., 2023 ; Griebler et al., 2017; McCabe et al., 2023 ; Mitra, 2004 ; Sprague Martinez et al., 2016)

Outcomes of student engagement initiatives related to mental health promotion and literacy for students:

- reduced stigma of mental health problems and mental illnesses

- reduced stigma towards accessing services and supports

- increased mental health literacy

(Griebler et al., 2017)

Outcomes of student engagement in mental health and well-being initiatives for caring adults, schools, and systems:

- Enhanced information and understanding of students’ needs and wants to allow for better identification and support of mental health challenges and barriers to accessing support.

- New perspectives in decision making and creative solutions to address mental health issues.

- Improved accuracy and relevancy of mental health initiatives.

- Increased use of mental health programs/services and more effective dissemination of information related to mental health and well-being.

- Strengthened relationships with students contributing to a more supportive school environment.

(Khanna & McCart, 2007; Sprague Martinez et al., 2016; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2017; Griebler et al., 2017; McCabe et al., 2023; Ramey et al., 2017)

For this resource, the terms “student engagement” and “student” are used rather than “youth engagement” or “youth,” respectively. As this resource has been developed for use within schools, children and youth are invited to share their lived experience, expertise, and voice related to their role as a student. It is important to remember that the student role reflects only a general age group, and among students, there is great diversity (e.g., developmental stage, socioeconomic status, culture, abilities and disabilities, gender, sexuality, ethnic origin, and many more). Outside their role as students, children and youth live vibrant lives and carry many other roles and experiences that can influence their perspectives and self-expression.

Dworkin, J. B., Larson, R., & Hansen, D. (2023). Adolescents’ Accounts of Growth Experiences in Youth Activities. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 32, 17-26. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021076222321

Griebler, U., Rojatz, D., Simovska, V., & Forster, R. (2017). Effects of student participation in school health promotion: A systematic review. Health Promotion International, 32(2), 195-206. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dat090

Khanna, N., & McCart, S. (2007). Adult Allies in Action. Centre of Excellence for Youth Engagement. Retrieved July 27, 2023, from https://www.studentscommission.ca/assets/pdf/tools/en/public/Adults_Allies_in_Action.pdf

McCabe, E., Amarbayan, M., Rabi, S., Mendoza, J., Naqvi, S. F., Thapa Bajgain, K., Zwicker, J. D., & Santana, M. (2023). Youth engagement in mental health research: A systematic review. Health Expectations, 26, 30-50. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13650

Mitra, D. L. (2004). The Significance of Students: Can Increasing “Student Voice” in Schools Lead to Gains in Youth Development? Teachers College Record, 106(4), 651-688. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9620.2004.00354.x

Ontario Ministry of Education (2023). Policy/Program Memorandum 169. https://www.ontario.ca/document/education-ontario-policy-and-program-direction/policyprogram-memorandum-169#foot-7

Public Health Agency of Canada (2020). About mental health. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/about-mental-health.html

Public Health Agency of Canada (2022). Mental Illness. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/chronic-diseases/mental-illness.html

Ramey, H. L., Lawford, H. L., & Vachon, W. (2017). Youth-Adult Partnerships in Work with Youth: An Overview. Journal of Youth Development, 12(4). https://doi.org/10.5195/jyd.2017.520

Sprague Martinez, L., Richards-Schuster, K., Teixeira, S., & Augsberger, A. (2016). The Power of Prevention and Youth Voice: A Strategy for Social Work to Ensure Youths’ Healthy Development. Social Work, 63(2), 135-143. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/swx059

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2019). Meaningfully engaging with youth: Guidance and training for UN staff. https://www.un.org/development/desa/youth/wp-content/uploads/sites/21/2021/05/Meaningfully-engaging-youth-Guidance-training-UN-staff.pdf

Foundations of Effective Student Engagement

The foundations of student engagement outlined below are the cornerstones for activities designed to foster and support meaningful and authentic participation, leadership, and agency amongst students. These foundations can help caring adults create and maintain environments and opportunities that lead to authentic student engagement and are especially important when considering activities related to mental health and wellness promotion at school.

Identity-affirming approaches are foundational to effective student engagement

Identity-affirming student engagement recognizes, validates, and respects students’ intersecting identities, backgrounds, and experiences. It involves dismantling systemic barriers to engagement, adapting initiatives to best meet students’ wants and needs, and creating an environment where students feel they can show up as their whole selves. This work is necessary to promote equity in student engagement opportunities and to support students’ sense of belonging, purpose, and well-being. In the graphic above, identity-affirming approaches are shown to be wrapped around every student to provide a visual reminder that high-quality and effective student engagement begins with each unique student in mind, centring especially those who experience marginalization and/or oppression so that space is intentionally created for their voices to be heard.

This is particularly important for student engagement initiatives that promote mental health at school because understandings and ideas for supporting wellness can be enhanced when diverse perspectives and ways of knowing and being are included in the planning and delivery of initiatives. Students can bring ideas that support strengths found in culture, faith, and community to help ensure a breadth of offerings. When students see others like them involved in mental health leadership, they may be more open to getting involved personally, and taking time to nurture their mental health.

- Recognize the interconnected nature of students’ identities and the presence of social barriers that often intersect and intertwine in their lives and may impact their sense of wellness.

- Understand that stigma related to mental health, such as cultural understandings of mental health, fear of judgement, or lack of trust, may prevent young people from stepping forward to get involved in wellness promoting activities at school.

- Note the systems of oppression that impact many students and how those impacts can be barriers to engagement at school. Work to disrupt and remove barriers to engagement.

- Understand that individual students cannot be representatives for a group of students, but they can bring strengths and ideas that may also resonate with others.

- Critically reflect on your practice, explore, and understand your identities and how who you are impacts the work you do and the relationships you have.

Reflect:

- What systemic or institutional forms of oppression or stigma might impact students, and how can you actively work to disrupt and remove these barriers to engagement?

- How can you better acknowledge and celebrate the strength and diversity of identities and experiences that students bring?

- How have you critically reflected on your own identities and how they might influence your interactions with students and the work that you do?

To support you in reflecting on your own personal values, beliefs and biases, check out:

To learn more about identity-affirming school mental health, check out:

Flexible

Flexibility is necessary to support students’ agency over their participation in various engagement activities. The degree of engagement a student chooses, and any changes in their level of involvement, can depend on many factors, such as interests, experiences, time commitments, and the demands of everyday life.

- Provide a variety of opportunities that enable students to choose their level of involvement and responsibility.

- Offer engagement opportunities at different times of the day, week, or year to accommodate students’ varying schedules and commitments.

- Encourage open and ongoing dialogue with students to understand their evolving wants and needs.

- Understand that some students who volunteer to help with wellness promotion and stigma reduction at school may themselves be struggling with a mental health problem or may live closely with someone who is. Encourage healthy boundaries and self-care so they can be at their best while participating at a level that is right for them.

Reflect:

- How well are you accommodating students’ interests, experiences, and everyday commitments?

- How effectively are you providing various engagement opportunities across degrees of engagement?

- How are you supporting students to adjust their level of engagement as needed?

Strength-based

Strength-based student engagement recognizes that every student possesses unique strengths, skills, and abilities. These can be nurtured and applied to support students’ skill development, self-confidence, and engagement.

- Recognize and respect that students are experts about themselves.

- Offer opportunities for students to showcase their strengths and abilities, develop new skills, and build their confidence.

- Normalize mistakes and offer students support as they exercise their strengths, skills, and abilities.

- Keep the focus on mental health and wellness promotion, rather than on topics that are beyond the scope of student knowledge and skills (e.g., avoid initiatives related to mental illnesses or suicide prevention, or those requiring students to take on a peer support / counseling role).

Reflect:

- How can you build in time and opportunities to learn about students’ skills and things they want to practice? How can you leave space for students to try?

- What strengths, skills, and abilities do you and the students bring to the group? How do they complement each other? How can you learn from each other?

- What opportunities can you provide students to showcase their strengths, skills, and abilities?

Informed

Informed student engagement refers to selecting relevant activities and evaluating initiatives alongside students. Having initiatives that are informed by students and accountable and transparent to students helps to ensure that they are responsive, impactful, and meaningful.

- Recognize that students know what students need. Listen to what is important to them.

- Involve students in developing monitoring, evaluation, and feedback processes to support their skill development and sense of ownership.

- Evaluate outcomes to celebrate successes and identify areas for improvement to enhance the impact of student engagement initiatives.

Reflect:

- In what ways are you fostering student-driven initiatives and ideas? How comfortable are you with outcomes that might differ from your initial expectations?

- How are you supporting student ideas in ways that are supportive for all participants?

- How are you actively involving students in the development of your monitoring, evaluation, and feedback processes?

Evolving

Evolving in the context of student engagement refers to the continuous process of adapting and changing strategies, approaches, and initiatives. Being informed provides the necessary knowledge and insight, and evolving is the practice of translating that information into meaningful change. This process ensures that student engagement initiatives remain responsive and tailored to students, fostering more inclusive and impactful experiences.

- Recognize that the student audience and their wants, needs, ideas, and strengths continue to change and evolve.

- Lead with students’ desires and give room for student-driven initiatives and ideas; these outcomes might not be exactly as you had imagined at the beginning and that’s okay!

Reflect:

- How have the wants, needs, ideas, and strengths of your student audience changed since the inception of your engagement initiatives? How are you staying attuned to these changes?

- What realities or changes in the local or global context may be impacting student participation in student engagement initiatives?

- How are you growing the initiative as some students join the work and others move on?

Degrees of Student Engagement in School Mental Health Initiatives

Students as leaders, partners, contributors, and consultants

Across the degrees of engagement, caring adults in the school have an important role in ensuring student support and safety. This is particularly important when students are leading or partnering in school-based mental health initiatives. For more see Actions of a Caring Adult in Student Engagement Initiatives Related to Mental Health and Special Considerations for School-Based Mental Health Promotion and Literacy Initiatives.

Differing degrees of participation offer students different skills, commitment requirements, and influence over the outcomes. In #HearNowON for 2021 students shared that leadership opportunities should be broadened to include and celebrate many different leadership styles. As such, diversity in opportunities for students to engage is crucial in a school and system. It enables students to contribute to the initiatives that excite them and best meet their interests and capacities.

Students may wish to get involved deeply in mental health or other initiatives at school, or they may want to participate more peripherally or less frequently because of other priorities in their lives. When we create room for flexible participation, more students can contribute.

Student engagement can take many forms, with different degrees of participation possible, depending on the initiative and its stage of implementation. Four broad ways of engaging students, to varying degrees, in school-based initiatives are described below (i.e., students as leaders, partners, contributors, or consultants).

| Students as leaders | |

|---|---|

| Initiation: | Initiated by students. |

| Engagement: | Students are responsible for all phases of a project or program (e.g., planning, implementation, evaluation). Note: caring adults can be facilitators to support students in achieving their goals and set parameters within which students can work. |

| Control over outcome: | Students identify the issues of concern and control the process and outcome. |

| Caring adult role: | Caring adults assist students in carrying out all phases of a project or program and ensure student support and safety. Caring adults may also help students secure support from school administration before proceeding. |

| Examples | Students lead a project on mental health stigma reduction. |

| Students as partners | |

|---|---|

| Initiation: | Initiated by students, caring adults, or both. |

| Engagement: | Students are engaged in an active partnership and open dialogue throughout all stages (e.g., decision-making, planning, implementation, and evaluation). |

| Control over outcome: | Students influence, challenge, and engage with both the process and outcome. |

| Caring adult role: | Caring adults partner with students to carry out all phases of the project or program. |

| Examples | Students partner with caring adults to carry out a project designed to help their peers manage stress related to tests and exams using the Student MH LIT module on this topic. |

| Students as contributors | |

|---|---|

| Initiation: | Initiated and managed by caring adults. |

| Engagement: | Students are invited to offer their ideas and perspectives at key points in the project (e.g., decision-making, planning, implementation, evaluation). |

| Control over outcome: | Students influence processes and outcomes without having direct control. |

| Caring adult role: | Caring adults carry out all phases of a project or program, facilitating student participation and voice in particular phases of the project or program. |

| Examples | Students participate in a project working group designed to help welcome newcomers to the school community. |

| Students as consultants | |

|---|---|

| Initiation: | Initiated and managed by caring adults. |

| Engagement: | Students are consulted for their ideas and perspectives in a specific or limited way. |

| Control over outcome: | Students influence outcomes without having direct control. |

| Caring adult role: | Caring adults carry out all phases of a project or program and include student voices in particular aspects of the project or program. |

| Examples | Students complete surveys or participate in student forums or focus groups related to creating mentally healthy school environments for every student. |

Model adapted from: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2019). Meaningfully engaging with youth: Guidance and training for UN staff

Case studies

Adult ally: A caring adult who has been identified as a supportive person by the students themselves.

Affinity space: Spaces typically reserved for individuals who share similar identities. The intention of the space or group is for people to feel comfortable showing up in their most authentic expression alongside others with similar experiences to create a level of protection where individuals in the space can share and feel validated.

Caring adult: An adult who listens to, supports, advocates for, and works with young people. In the context of student engagement, they acknowledge their role as a partner with students and actively work to:

- create supportive and collaborative spaces;

- put aside biases and assumptions; and

- ensure that students’ voices and perspectives are heard, validated, considered, and amplified.

Caring adults may not always be explicitly named as allies by students, but their actions and attitudes show their commitment to meaningful student engagement and the growth and success of students.

Mental health: Mental health is the state of an individual’s psychological and emotional well-being. It is a necessary resource for living a healthy life and a main factor in overall health. Good mental health allows you to feel, think and act in ways that help you enjoy life and cope with its challenges. (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2023; Public Health Agency of Canada, 2020)

Mental illness: Mental illnesses are associated with alterations in thinking, mood or behaviour that cause significant distress and impaired functioning in one or more areas, such as school, work, social or family interactions or the ability to live independently. (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2023; Public Health Agency of Canada, 2022)

School-based mental health promotion initiatives: Any effort that builds student wellness at school. Initiatives may be school or class-wide and are designed to build on student strengths to develop skills, supports, and ways of wellness.

Mental health literacy initiatives: Initiatives that aim to enhance knowledge about mental health and well-being, nurture mentally healthy attitudes, reduce stigma, assist with identifying signs of mental health and substance use problems, and/or build awareness of local resources and supports.

A sincere thank you to the following who participated in consultations and working groups to help create and shape this toolkit!

Andrea Bewcyk-Evans, Elementary Student Success, Simcoe County District School Board

Ashley Wall, Child and Youth Counsellor Placement Student, Halton District School Board

Avneet Dourka, Grade 9 student, ThriveSMH

Camila Gonzalez, Senior Child and Youth Care Practitioner, Dufferin-Peel Catholic District School Board

Chantelle Quesnelle, Mental Health Lead, Simcoe Muskoka Catholic District School Board

Cheryl Pearson, Multi-disciplinary Itinerant Teacher, Lambton Kent District School Board

Emma Blundy, Multi-Disciplinary Itinerant Teacher, Lambton Kent District School Board

Jennie Melo-Jordan, Teacher/Department head, Algonquin and Lakeshore Catholic District School Board

Jenny Marino, Mental Health Lead, Upper Grand District School Board

Jillian Hutter, Itinerant Special Education Teacher, St. Clair Catholic District School Board

Karen Trotter, Conseillère pédagogique santé et bien-être des élèves M-12, Conseil scolaire catholique Providence

Karen Watt, IB Coordinator/Guidance Counselor, Lakehead District School Board

Kelsey Foster, Health Promotion Officer, St. Clair Catholic District School Board

Kirin Alcordo, Grade 12 student, ThriveSMH

Lillian Keys-Brasier, Grade 12 student, ThriveSMH

Loli Massoda, Grade 12 student, ThriveSMH

Lori Beckstead, Core Teacher, Equity and Mental Health Lead, Catholic District School Board of Eastern Ontario

Louise Pike, Well-being Facilitator, Simcoe County District School Board

Marie Hull, Itinerant Special Education Teacher, St. Clair Catholic District School Board

Marie-Eve Demers, Leader en santé mentale, Conseil scolaire catholique Providence

Nicole Hamilton, Principal, Upper Grand District School Board

Reah (Hyun Ju) Shin, Child and Youth Counsellor Supporting 2S/LGBTQIA+ students, Halton District School Board

Saede Annoh-Waithe, Grade 12 student, ThriveSMH

Steph Gunning, Vice-Principal, Ottawa Catholic School Board

Suzie Kisimba, Leader en Santé Mentale, Conseil scolaire catholique MonAvenir

Tracy Hunter, K-12 Program Lead for Student Success, Transitions, and Destreaming, Upper Grand District School Board

Varisha Shakeel, Grade 10 student, ThriveSMH

Yohou Micheline Rabet, Leader en santé mentale, Conseil scolaire Viamonde