The promise of school mental health

Wellness at school

Every day, in classrooms across Ontario, there are opportunities to inspire purpose, hope, meaning and belonging amongst students. When we start early in life and reinforce skills and habits that promote mental health within caring classroom settings, we can set students up for success, and may help to prevent or minimize the burden of future mental health problems.

Research has shown that school-based mental health interventions, delivered universally or in targeted ways by school staff, can reduce students’ experiences of mental health problems. Embedding programming into daily practice appears to yield the highest benefits.

Mental health and learning

When students are feeling mentally well, they’re more available for learning. Research has linked participation in high-quality social-emotional learning at school with students’ emotional wellness and their academic achievement.

Students who receive systematic, active, and focused social-emotional skill instruction perform better on standardized academic tests than those who have not. Also, targeted intervention for students at risk can help to prevent or improve some learning problems at school.

The return on investment of mental health programs at school

Effective school mental health practices make economic sense. Across many jurisdictions, analyses have shown that investing in mental health promotion early yields a strong return. For example, economic models from the UK show a significant return on investment for social emotional learning (83.73 £ Return/£ Invested) and anti-bullying programming (14.35 £ Return/£ Invested). Studies in Canada indicate particular value for early years mental health promotion ($6-16 Return/$ Invested). It has also been noted that investments in school mental health yield cost savings in other sectors like health and justice.

Understanding mental health and mental illnesses

Mental health and mental illnesses aren’t the same things, though the terms are sometimes confused and used interchangeably.

What is mental health?

Mental health is a positive state of wellness and flourishing. When we are mentally healthy, we enjoy life, explore and take healthy risks, manage adversity, and find ways to contribute to the world around us. It is something we all want for ourselves, our children, and others whom we love and care about.

Although there are many definitions of mental health, a particularly thoughtful and comprehensive understanding is reflected in the First Nations Mental Wellness Continuum Framework, which suggests that mental health and well-being is inspired through “a balance of the mental, physical, spiritual, and emotional” and that everyone, even the most vulnerable or mentally ill, has an opportunity to live as a whole and healthy individual.

Balance can be “enriched as individuals have purpose in their daily lives… hope for their future… a sense of belonging and connectedness within their families, to community, and to culture and … a sense of meaning and an understanding of how their lives and those of their families and communities are part of creation and a rich history (p. iv).”

Everyone experiences difficulties with their emotions from time to time. It’s good to remember that even when we, or our children, are experiencing more serious mental health concerns, recovery and wellness are possible

What are mental illnesses?

Mental illnesses include severe and persistent difficulty with thoughts, emotions or behaviours that causes distress and interfere with day-to-day functioning. The brain governs thoughts, emotions, and behaviours. Mental illnesses are therefore often thought of as being a disease of the brain. While this is true, in part, mental illnesses are also influenced by a range of factors and experiences, including:

- Genetics

- Social determinants of health (e.g., income and social status, physical environments, race and racism, access to health services)

- Acute or persistent trauma

How common are mental illnesses?

Extreme forms of mental illness are rare (e.g., one percent of the Canadian population suffers from schizophrenia). Other types of mental health disorders are more common.

Because difficulties with things like anxiety, attention, or mood are experiences we all have from time to time, it can be challenging to determine if the problem is simply a typical reaction or normal fluctuation, or if it’s something more serious requiring treatment.

Distinguishing between a mental illness and the regular ‘ups and downs’ of adolescence is even harder. For younger children, mental health concerns often go undiagnosed because they don’t always express their feelings and thoughts in a way that adults can respond to.

Rule of thumb: If you notice a change in behaviour, emotions, or thoughts that lasts more than two weeks, is distressing and is negatively impacting day-to-day living, it is time to get it checked out.

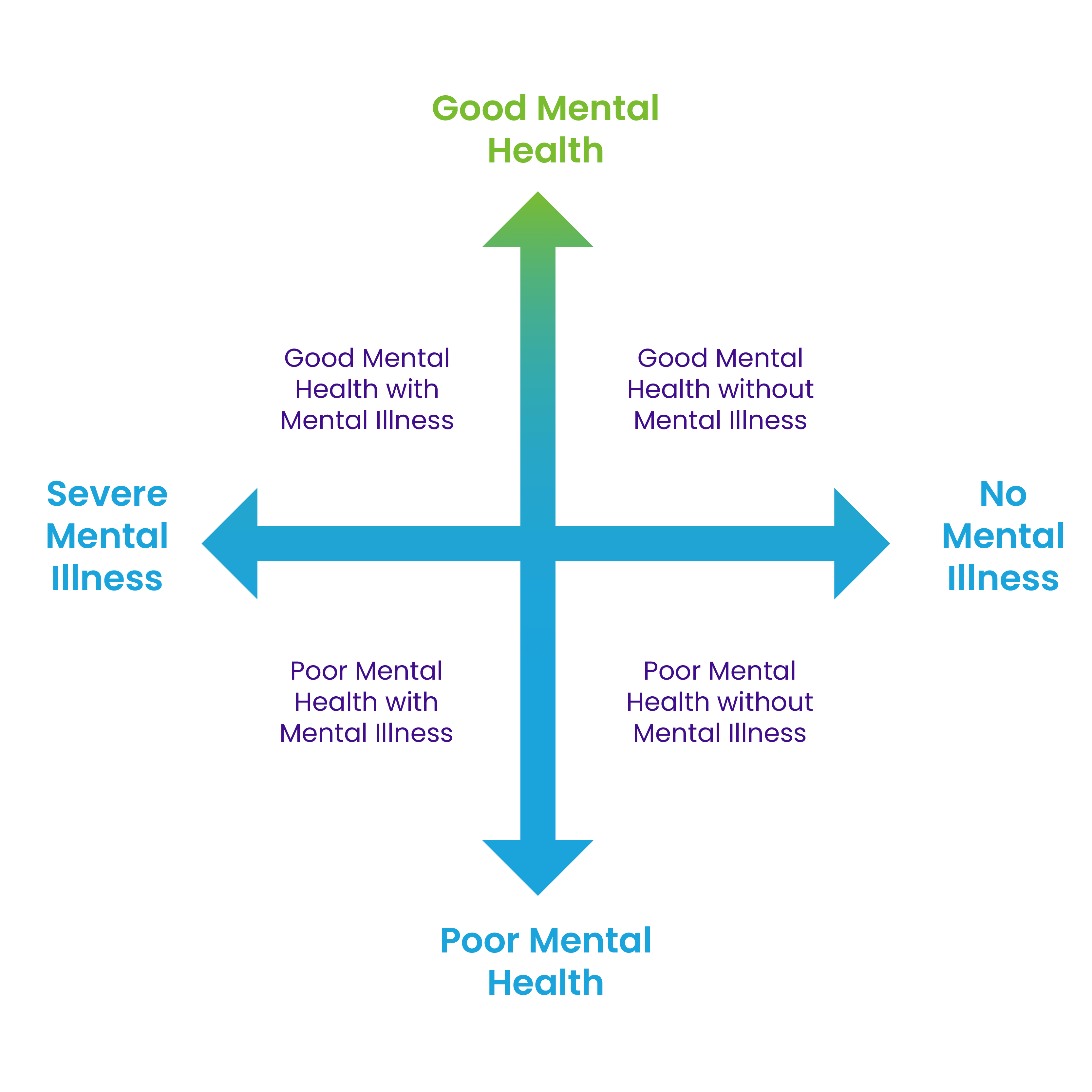

What’s the relationship between mental health and mental illness?

Mental health is more than the absence of mental illnesses. Even when experiencing a mental illness, it’s possible to feel mentally well. It’s also possible to feel mentally unwell and not have a mental illness. The dual continuum model explains the relationship.

This graphic is a visual representation of the dual continuum model of mental health. The graphic is divided into 4 quadrants with a two-sidedarrow running through the middleboth verticallyand horizontally. The arrows represent a continuum on both axes. The north south axis is labelled “good mental health” on the top and “poor mental health” on the bottom. The east west axis is labelled “no mental illness” on the right and “severe mental illness” on the left. The upper right quadrant reads “good mental health without mental illness”. Moving clockwise from here the lower right quadrant reads “poor mental health without mental illness. The bottom left quadrant reads “poor mental health with mental illness”. The upper left quadrant reads “good mental health with mental illness”.

This short video from the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) elaborates on this idea, and adds dimension, through the dual continuum model.

Quick facts about mental illness

- About 1.2 million children and youth are affected by a mental illness. Eighteen to 22 per cent of students in Ontario meet the criteria for a mental health illness or concern.

- More students are expressing a need for help with psychological distress, but only 22 – 34 per cent of children and youth who have a mental health problem receive needed clinical services.

- In 2021, 62 per cent of grade 7-12 students rated their mental health as good to excellent. 39 per cent of students felt that the pandemic negatively affected their mental health “very much” or “extremely”.

- Since the pandemic began, rates of psychological distress among young people, including symptoms of anxiety, depression, and other mental health concerns have increased globall.

- There was a significant increase in the number of children and youth seeking help for eating disorders in both Ontario and Canada.

- In Canada,17 – 40 per cent of children and youth will seek formal mental health service.

- On a positive note, 44 per cent of children and youth in Ontario would seek help for their mental health needs at school.

- With appropriate care and support, people who have a mental illness can experience positive mental wellness.

The continuum of mental health support at school

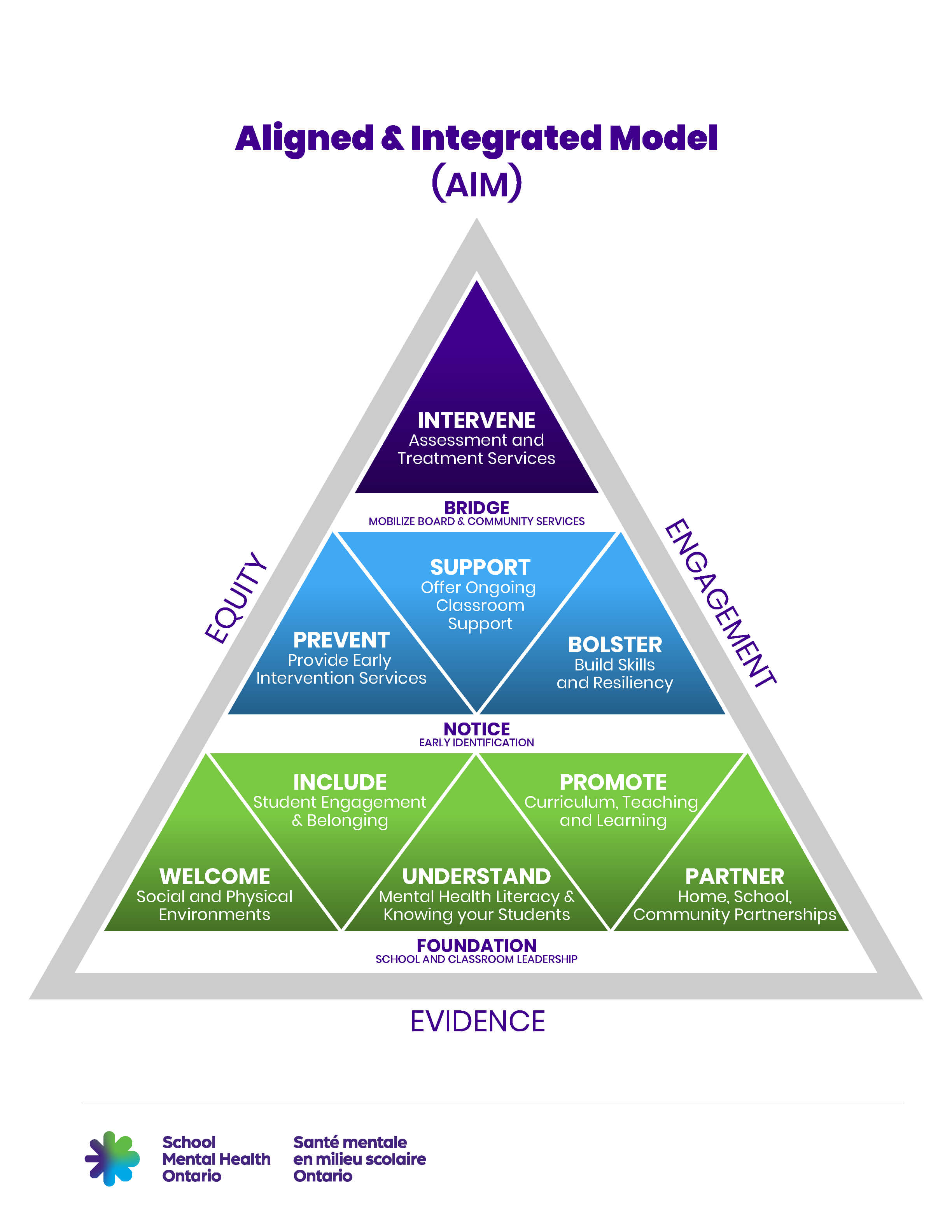

As noted above, schools are an excellent place to promote mental health, notice concerns early, offer services, and provide ongoing support. To organize the various supports and services most suited to the school setting, leaders in this area describe a continuum of care, often called a “Multi-Tiered System of Support”. In Ontario, we depict this continuum using the AIM model.

The Aligned and Integrated Model or AIM is a triangle with three equal sides that shows the three levels of student mental health support in Ontario. The bottom of the triangle is the Foundation and includes school and classroom leadership. It’s divided into the following five sections:

Welcome – school and classroom physical environments

Include – student engagement and belonging

Understand – Mental health literacy and knowing your students

Promote – Curriculum, teaching and learning

Partner – Home, school, community partnerships

The second level is Notice and represents early identification. It’s divided into the following three segments:

Prevent – Provide early intervention services

Support – Offer ongoing classroom support

Bolster – Build skills and resiliency

The third level is the top of the triangle. It is Bridge and represents mobilizing board and community supports. It includes one segment:

Intervene – Assessment and treatment services The words equity, engagement and evidence appear around the graphic.

This model helps to organize mental health promotion efforts offered in a universal way for all students (Tier 1), services for students who may be at risk and needing a “higher dose” of targeted skill development (Tier 2) and supports for students who have a diagnosable mental health problem who need treatment and ongoing care (Tier 3).

Mental health promotion at school

An essential ingredient in mental health promotion is ensuring a welcoming, inclusive, caring classroom environment where every student knows and feels that they belong. Educators and other school staff can help students learn about mental health and develop healthy habits. Within mentally healthy schools and classrooms, we:

- nurture identity, relationships and a sense of belonging

- help students learn how to manage stress and maintain an optimistic outlook

- teach about mental health in developmentally appropriate ways

- emphasize critical thinking skills like goal setting, problem-solving, task focus, and decision-making

- model healthy habits

- reduce stigma

- connect students with additional support when needed

Many good initiatives, speakers, and programs can help mental health promotion, but a thoughtful approach to selection is required. Mental health programming can be risky, and sometimes well-intentioned approaches can cause harm. If you aren’t sure about an approach, consult your board mental health leader. We also offer decision support tools to help select mental health programming.

School Mental Health Ontario has a growing suite of social-emotional learning and mental health literacy tools and resources . All our resources are evidence-informed and implementation sensitive.

Have an idea for a new mental health promotion initiative? Contact us and we can consider this for our Innovation and Scale-Up Lab where new ideas are tested for Ontario schools.

Early identification of mental health concerns

For most students, everyday practices and caring support will be enough to help them flourish. Some students may need more support. Educators and other staff members may notice small changes in student behaviour and emotions over time. They can recognize the early signs of mental health concerns or mental illness, help students to describe how they’re feeling and connect them with appropriate support. Educators are not mental health professionals, and cannot diagnose a problem in this area, but they can observe and connect.

Prevention and early intervention services

In addition to ongoing classroom support for students at risk, such as appropriate accommodations and modifications to address associated learning and emotional/behavioural needs, schools are well-positioned to provide prevention and early intervention services for students with mild-to-moderate mental health concerns.

Most school boards across Ontario have regulated mental health professionals, such as school social workers, psychologists, and psychological associates, who are trained to deliver evidence-informed preventive interventions.

School Mental Health Ontario is creating a growing suite of structured psychotherapy approaches to help in enhancing the quality and consistency of Tier 2 services. These approaches are evidence-informed and implementation-sensitive.

Intensive intervention and ongoing support

In Ontario, schools are the most common place children and youth receive mental health support. And while ideally positioned for mental health promotion, prevention and early intervention services, schools are not ideally suited to provide intensive therapeutic intervention.

When students are struggling with mental illness, it’s critical that they receive the types of supports that are offered within a community or healthcare setting. School staff help to identify when students require more support than can be offered through prevention and early intervention services, and help students and families to access this additional help. School staff continue to support students through and from services, reinforcing skills and strategies that clinical settings have established with them.

Some students will not, or cannot, access clinical services, but they still come to school. School-based regulated mental health professionals, school staff, and parents/caregivers need to coordinate to wrap around supports as best as they can to help the student to be successful and well. School-based crisis support also needs to be available in case an emergency were to arise.

By creating mentally healthy school environments, introducing high-quality mental health promotion, offering prevention and early intervention services, and ensuring a safety net for students dealing with mental health concerns, schools can fulfill the promise and play a strong role in keeping young Ontarians mentally well.

References

Pulimeno, M., Piscitelli, P., Colazzo, S., Colao, A., & Miani, A. (2020). School as ideal setting to promote health and wellbeing among young people. Health promotion perspectives, 10(4), 316–324. https://doi.org/10.34172/hpp.2020.50 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7723000/)

Short, K.H. (2016). Intentional, explicit, systematic: Implementation and scale-up of effective practices for supporting student mental well-being in Ontario schools, International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 18:1,33-48, DOI: 10.1080/14623730.2015.1088681

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/citedby/10.1080/14623730.2015.1088681?scroll=top&needAccess=true

Sanchez, A.L., Cornacchio, D., Poznanski, B., Golik, A.M., Chou, T., Comer, J.S. (2018). The Effectiveness of School-Based Mental Health Services for Elementary-Aged Children: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 57:3, 153-165, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2017.11.022. https://www.jaacap.org/article/S0890-8567(17)31926-3/fulltext

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: a meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child development, 82(1), 405–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21291449/

Roberts, G., Grimes, K. (2011). Return on Investment: Mental Health Promotion and Mental Illness Prevention, Canadian Policy Network at the University of Western Ontario. https://cpa.ca/docs/File/Practice/roi_mental_health_report_en.pdf

Knapp, M., McDaid, D., Parsonage, M. (Eds.). (2011). Mental health promotion and mental illness prevention: The economic case. Department of Health London. https://kar.kent.ac.uk/32450/1/Knapp_et_al__MHPP_The_Economic_Case.pdf

Government of Canada. (2014, December). First Nations mental wellness continuum framework – Summary report. Health Canada and Assembly of First Nations. https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1576093687903/1576093725971

First Nations Mental Wellness Continuum Framework. (2015). Summary Report. https://thunderbirdpf.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/24-14-1273-FN-Mental-Wellness-Framework-EN05_low.pdf

Government of Canada. (n.d.) Mental Illness. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/chronic-diseases/mental-illness.html

Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System. Schizophrenia: Age-standardized prevalence, percent, 2016, 2019. (n.d.) https://health-infobase.canada.ca/ccdss/data-tool/Comp?G=35&V=5&M=1

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Cautionary statement for forensic use of DSM-5. In Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Keyes CLM. The mental health continuum: from languishing to flourishing in life. J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43(2):207–222.

Mental Health Commission of Canada. (n.d.). Children and Youth. https://mentalhealthcommission.ca/what-we-do/children-and-youth/

Ontario Student Drug Use and Health Survey [OSDUHS] (2021). The Well-Being of Ontario Students: Findings from the 2021 Ontario Student Drug Use and Health Survey – Summary Report.

https://www.camh.ca/-/media/files/pdf—osduhs/2021-osduhs-report-summary-pdf.pdf

The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory. (2021). Protecting Youth Mental Health. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-general-youth-mental-health-advisory.pdf

Toulany, A., Kurdyak, P., Guttmann, A., Stukel, T. A., Fu, L., Strauss, R., Fiksenbaum, L., & Saunders, N. R. (2022). Acute Care Visits for Eating Disorders Among Children and Adolescents After the Onset of the COVID-19. Pandemic. Journal of Adolescent Health, 70(1), 42–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.09.025

Agostino, H., Burstein, B., Moubayed, D., Taddeo, D., Grady, R., Vyver, E., Dimitropoulos, G., Dominic, A., & Coelho, J. S. (2021). Trends in the Incidence of New-Onset Anorexia Nervosa and Atypical Anorexia Nervosa Among Youth During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Canada. JAMA Network Open, 4(12), e2137395. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.37395

Georgiades, K., Duncan, L., Wang, L., Comeau, J., Boyle, M. H., & 2014 Ontario Child Health Study Team. (2019). Six-month prevalence of mental disorders and service contacts among children and youth in Ontario: Evidence from the 2014 Ontario child health study. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 64(4), 246–255. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743719830024

Offord Centre for Child Studies (2015). School Mental Health Surveys: A study examining the association between the school environment and student mental health and well-being. https://ontariochildhealthstudy.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/SMHS-report-PROVINCIAL-FINAL.pdf

Stoiber, K., Gettinger, M. (2016). Multi-Tiered Systems of Support and Evidence-Based Practices. In: Jimerson, S., Burns, M., VanDerHeyden, A. (eds) Handbook of Response to Intervention. Springer, Boston, MA.

Specht, J. A. (2013). Mental Health in Schools: Lessons Learned From Exclusion. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 28(1), 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/0829573512468857

Georgiades K, Duncan L, Wang L, Comeau J, Boyle M & 2014 OCHS Team Canadian Journal of Psychiatry (2019). Six-Month Prevalence of Mental Disorders & Service Contacts among Children in Ontario. Retrieved from: https://ontariochildhealthstudy.s3.amazonaws.com/uploads/OCHS_Prevalance_Brief_March-26-2019_Final_Print.pdf

School and Community System of Care Collaborative. (2022). Right time, right care: Strengthening Ontario’s mental health and addictions system of care for children and young people. Retrieved from: https://cmho.org/wp-content/uploads/Right-time-right-care_EN-Final-with-WCAG_2022-04-06.pdf