Substance use and addiction

Young people may experiment with substances at some point during their development. Their experimentation and use may remain at a controlled level, or their use may become excessive and interfere with social and psychological functioningi. Alcohol and cannabis are the substances most frequently tried by youthii iii . Consideration of social context and historically oppressed groups are important factors to consider in the early experimentation of substance use , as well as with intervention.

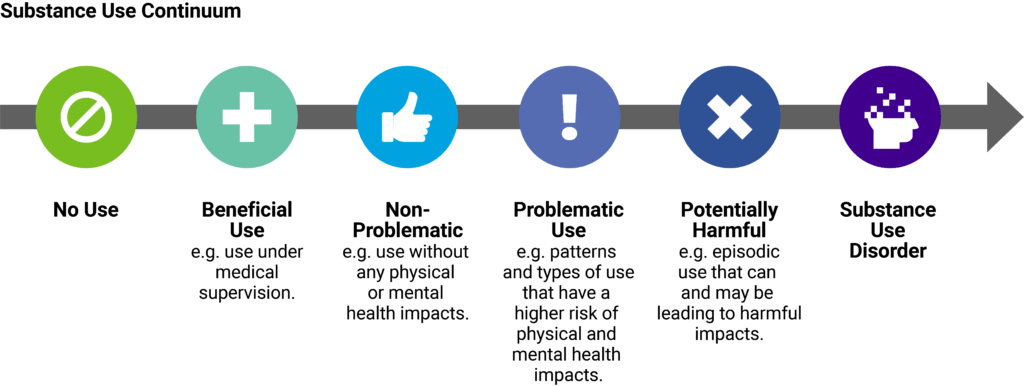

Continuum of substance use

Substance use occurs along a spectrum (commonly called a continuum of use) ranging from no use at all to experiencing a substance use disorder. A comprehensive approach requires evidence-based strategies that address the needs of all students, regardless of where they fall on the continuum of use. Note that problematic substance use and mental health problems often co-occur, regardless of which one comes first.

As an educator, you have a role to play in promoting resilience, noticing when a student may be struggling with a mental health problem, and providing ongoing caring support in the classroom.

As an educator, you have a role to play in promoting resilience, noticing when a student may be struggling with a mental health problem, and providing ongoing caring support in the classroom.

Resources for educators

How to help students

Activities that promote student well-being and connectedness at school can help to prevent problematic substance use. The work you do to create and sustain a mentally healthy classroom is a key part of this.

You can also:

- Help students explore healthy ways to manage stress and feelings without the use of substances

- Help students explore substance-free activities, especially activities that facilitate relationships and a sense of belonging

- Provide students with opportunities to learn about substances through assignments, classroom debates or discussion of current events. The MH78 curriculum module on mental health, substance use and the relationship between them provides an opportunity to discuss risks, harms and healthy choices

- Remind students they have a choice if they’re feeling pressured to try something

- Suggest students talk to a trusted adult to understand more about a substance, how to reduce harm, and how to respond to peer pressure

- Encourage students to avoid or delay trying substances. Prioritizing prevention programs with young people can aid in delaying or avoiding substance use

- Remind students to never ride with a driver who is under the influence of alcohol, cannabis or another substance

- Have evidence-informed lower risk use guidelines for common substances available for students to take or for you to review together. CAMH and the Canadian Centre for Substance Use has guidelines for alcohol (for adults). Guidelines for cannabis use is available at CAMH for youth, and Canadian Centre for Substance Use for adults

Learn more about effectively increasing well-being to reduce prevent problematic substance through the Preventing Problematic Substance Use through Positive Youth Development resources.

It’s sometimes hard to detect problematic substance use. Some signs can look like typical youth behaviour. For example: i ii

- ignoring responsibilities at work, school, or home

- giving up activities that they used to find meaningful or enjoyable

- changes in mood (e.g., feeling irritable and paranoid)

- changing friends

- having difficulties with family members, friends, and peers

- being secretive or dishonest

- changing sleep habits, appetite, or other behaviours

- borrowing money or having more money than usual

Students showing possible signs of concerning substance use require additional opportunities to build resilience and coping skills. They may benefit from small group interventions delivered by school mental health professionals designed to promote protective factors and wellbeing. They may also benefit from community-based interventions for specialized treatment. In addition, there are things you can do in the classroom to provide caring support. For example:

- Provide a welcoming response to students when they arrive in class and promote a sense of belonging for all students

- Provide students with accurate, factual information about substances within the context of curriculum content

- Be aware of the potential harm of “scare” tactics

- Be a positive role model for students by modelling appropriate, respectful behaviour, providing guidance and support, and helping students to make good decisions

- Let students know that you will help them get the support they need if you are concerned

What to do if you’re concerned:

Remember, it’s not your role to diagnose a mental health or substance use problem or provide treatment. When you notice and document your observations, and connect in a caring and non-judgmental way, you can help the student get the support they need.

When to take action

- You’ve noticed changes in day-to-day functioning

- The signs of difficulty seem severe or prolonged

- The student or their family has expressed concern

What to do

- Follow your school board’s protocol for accessing mental health support. This may include:

- consulting with your principal, vice-principal or member of your school’s mental health leadership team

- discussing your observations with the student and/or their parent/guardian

- a referral for professional mental health support from school board personnel (e.g., school social worker or school psychologist)

- a referral for professional mental health support within the community

You are a critical part of the support process because you help with early identification. You will remain part of the student’s as they move to, through, and from professional mental health services.

Depending on the student’s needs, some or all of the practices listed above may be helpful. Working closely with the student, their family, and mental health professionals within the circle of support is the best way to ensure that classroom support meets the student’s mental health needs.

To summarize, if you are concerned about a student in your class, follow your school/board service pathways process. Not sure about the process? Ask your principal or contact your board mental health leader for more information.

From Drug Free Kids Canada, a Cannabis Talk Kit provides information for parents about how to talk with teens about cannabis.

The Canadian Centre for Substance Use and Addiction provides a guide for youth allies about engaging in conversations around cannabis called Talking pot with youth.

Canadian Students for Sensible Drug Policy created a resource which makes recommendations about cannabis called Sensible Cannabis Education: A Toolkit for Educating Youth.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8835119/

Squeglia LM, Jacobus J, Tapert SF. (2009). The influence of substance use on the adolescent brain. The Clinical EEG and Neuroscience, 40(1), 31-38. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2827693/

NIDA. 2023, December 12. Most Commonly Used Addictive Drugs. Retrieved from https://archives.nida.nih.gov/publications/media-guide/most-commonly-used-addictive-drugs on 2024, July 4

Hansen, J. & Hetzel, C. C. (2018). Exploring the addiction recovery experiences of urban Indigenous youth and non-Indigenous youth who use the services of the Saskatoon Community Arts Program. Aboriginal Policy Studies (Edmonton, Alberta, Canada),

(1). https://doi.org/10.5663/aps.v7i1.28525

Courtney KE, Mejia MH, Jacobus J. Longitudinal Studies on the Etiology of Cannabis Use Disorder: A Review. Current Addiction Reports. 2017;4(2):43-52. Available from: doi: 10.1007/s40429-017-0133-3.

Ali S, Mouton CP, Jabeen S, Ofoemezie EK, Bailey RK, Shahid M, Zeng Q. Early detection of illicit drug use in teenagers. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011 Dec;8(12):24-8. PMID: 22247815; PMCID: PMC3257983.

CAMH. (n.d.) Talking about and spotting substance use.

i Squeglia LM, Jacobus J, et Tapert SF. (2009)

ii Canadian Centre for Substance Use. (2023). Canada‘s guidance on alcohol and health. Final report.

iii National Institude of Druge Abuse. Most commonly used addictive drugs. *Note: Reference 7 on the cannabis guide

iv Hansen, J. & Hetzel, C. C. (2018). Exploring the addiction recovery experiences of urban

Indigenous youth and non-Indigenous youth who use the services of the Saskatoon Community Arts Program. Aboriginal Policy Studies (Edmonton, Alberta, Canada),

(1). https://doi.org/10.5663/aps.v7i1.28525

v Courtney KE, Mejia MH, Jacobus J. Longitudinal Studies on the Etiology of Cannabis Use Disorder: A Review. Current Addiction Reports. 2017;4(2):43-52. Available from: doi: 10.1007/s40429-017-0133-3.

vi Ali S, Mouton CP, Jabeen S, Ofoemezie EK, Bailey RK, Shahid M, Zeng Q. Early detection of illicit drug use in teenagers. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011 Dec;8(12):24-8. PMID: 22247815; PMCID: PMC3257983.

vii CAMH. (n.d.). Talking about and spotting substance use. https://www.camh.ca/en/health-info/guides-and-publications/talking-about-and-spotting-substance-abuse