Promising findings continue for Ontario students receiving Brief Digital Interventions

One of the many aims of school mental health services is to identify and support students with emerging or escalating mental health problems1. Because each student is different, regulated school mental health professionals, such as school social workers and psychological services staff, use a range of evidence-informed, culturally responsive approaches to respond to the needs of students they work with. These approaches vary based on a student’s mental health need, identity, and circumstances.

In the realm of lower-intensity offerings, within Ontario school boards, Brief Digital Interventions (BDI) were introduced in 2020-2021 as one way to help students experiencing mild mental health difficulties. This approach was designed by researchers at Harvard University and adapted for use in Ontario. This adaptation included a tool developed by researchers from the Offord Centre for Child Studies at McMaster University to help students measure their progress throughout the intervention.

If you aren’t familiar with this intervention, consider reading the following blog post: Brief Digital Interventions: Scalable, available brief mental health support in schools where you will learn more about:

- Why Coping Kits, which are used in BDI, were developed

- What the intervention process looks like

- How they are being adopted and adapted in Ontario school boards, and

- What the research says about its effectiveness

Promising findings in Ontario school boards2

During the 2021-2022, 2022-2023 and 2023-2024 school years, School Mental Health Ontario continued to partner with the Offord Centre for Child Studies and Harvard University to learn how the Brief Digital Interventions were being used within school boards, and if students who received this intervention reported fewer mental health concerns afterwards.

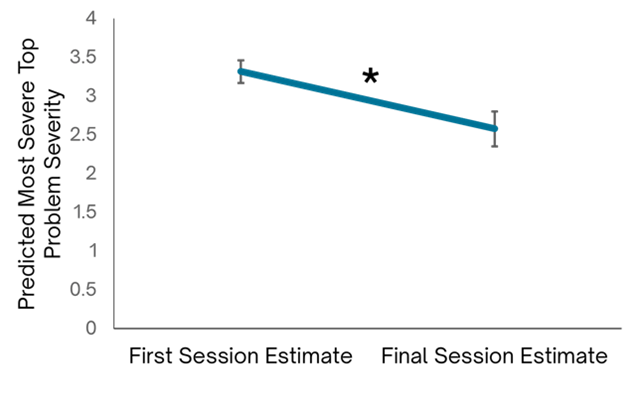

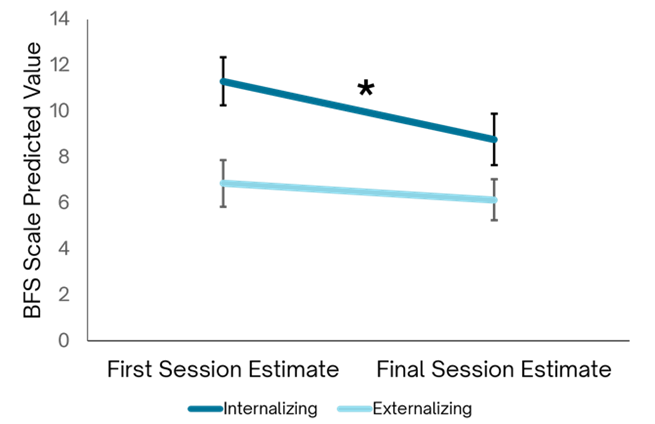

Findings show that students who received BDI in Ontario schools showed a statistically significant improvement in ratings of their self-identified top problems and their experience of anxiety and depressed mood. These findings are shown in the graphs below. These changes from before to after the brief intervention did not involve a control group, but they are consistent with findings of research that has used control groups3,4.

Figure 1. Pre-Post Top Problem Perceived Severity

A line graph displaying the change in perceived severity of the top problem from pre- to post-intervention. The y-axis represents severity on a scale from 0 to 4, while the x-axis has two data points labelled ‘First session estimate’ and ‘Final session estimate.’ The line connecting the two points slopes downward, indicating a decrease in perceived severity after the intervention. Error bars are present on both points.

Figure 2. Pre-Post Behaviour and Feelings Scale

A line graph showing changes in Behaviour and Feelings Scale scores from the first session estimate to the final session estimate. The y-axis represents scores on a scale from 0 to 14, while the x-axis has two points labeled ‘First Session Estimate’ and ‘Final Session Estimate.’ Two lines are plotted: a darker line representing internalizing behaviours, which starts around 12 and decreases slightly to around 9 by the final session, and a lighter line representing externalizing behaviours, which starts around 7 and also decreases slightly to around 6. Error bars are present on both lines at both points. A black asterisk above the dark line indicates a statistically significant reduction in internalizing behaviours.

Satisfaction: School mental health professionals

Of the 53 school mental health professionals that have taken part in the study, 42 provided feedback about their satisfaction with the intervention and its accompanying Progress Monitoring Tool (PMT). The majority of school mental health professionals agreed or strongly agreed that the Brief Digital Interventions allowed them to:

- individualize interventions for students (83.3%),

- be responsive to the needs and concerns of students (85.7%), and

- enhance the outcome of students that they work with (81%).

Most also agreed or strongly agreed that the Brief Coping Interventions Progress Monitoring Tool helped them to:

- identify what to focus on (90.5%),

- communicate with students their progress (88.1%), and

- include students when making decisions about intervention options and next steps (95.2%).

Students enjoyed seeing their dashboard and helpful discussions often ensued.

School social worker

Navigation was easy, the visual makes it easy to understand things quickly.

School social worker

Satisfaction: students

A small percentage (19.7%) of the 213 students who participated in the study provided feedback about their satisfaction and experience with the coping skills they learned. Of these, the vast majority agreed or strongly agreed with all the items of the survey, which included:

- I learned things from this coping kit that will help me (95.2%)

- I will use things I learned from this coping kit (95.2%)

- This coping kit will help other young people (95.2%)

Note: Coping kits are online learning modules that aim to bolster specific skills based on the student’s need. These include:

- Relaxation skills (Project Calm)

- Problem-solving skills (Project Solve)

- Reframing and realistic thinking strategies (Project Think)

- Trying something different (Project Opposite)

Rebranding the Brief Digital Interventions to reflect what we have learned so far

BDI was introduced in Ontario to meet the needs of students’ emerging mental health needs during the pandemic. This brief innovative approach was design to be accessible and used as part of virtual care, hence the term “Digital”. However, since the pandemic, school mental health professionals continued to use the online coping kits (which are integral to the intervention) in-person with students. Therefore, in order to better reflect the focus of the intervention, the name has been changed to Brief Coping Interventions.

Great resources I can use in sessions, very applicable for brief counselling in schools.

School social worker

More people to be trained across the province

Currently, there are 722 school mental health professionals from 66 boards who have received training for this intervention. If you are a regulated school mental health professional and you are interested in incorporating this approach in your practice, please reach out to your board’s mental health leader about upcoming training opportunities or contact Tracy Weaver at School Mental Health Ontario for more information at tweaver@smho-smso.ca.

- Hoover, S., & Bostic, J. (2021). Schools as a vital component of the child and adolescent mental health system. Psychiatric services, 72(1), 37-48.

- Offord Centre for Child Studies (2024). Evaluating Brief Digital Interventions for School-Aged Youth in Ontario Schools. Report prepared for School Mental Health Ontario.

- Schleider, J.L., & Weisz, J.R. (2017). Little treatments, promising effects: Meta-analysis of single-session interventions for youth psychiatric problems. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 56, 107-115.

- Fitzpatrick, O.M., Schleider, J.L., Mair, P., Harisinghani, A., Carson, A., & Weisz, J.R. (2023). Project SOLVE: Randomized, school-based trial of a single-session digital problem-solving intervention for adolescent internalizing symptoms during the coronavirus era. School